In the mid-19th century, the tragic fate of Sir John Franklin’s expedition gripped the world. In 1845, Franklin set out with two ships, Erebus and Terror, to chart the elusive Northwest Passage. Both vessels became trapped in the ice, and the entire crew was lost. The mystery surrounding their disappearance captured the public imagination and sparked decades of search expeditions—many of which contributed valuable knowledge about the Arctic.

These early trials paved the way for what became known as the Heroic Age of Polar Exploration. Figures like Fridtjof Nansen, who attempted to drift across the Arctic Ocean on the Fram, and Roald Amundsen, who not only completed the Northwest Passage but also reached the South Pole in 1911, pushed the limits of human endurance.

From Franklin’s doomed voyage to the triumphs of later explorers, the polar regions became both a stage for human drama and a source of groundbreaking scientific discovery. Their legacy reminds us that exploration is as much about perseverance in the face of hardship as it is about reaching distant horizons.

In the summer of 1845, Sir John Franklin, a veteran Royal Navy officer with decades of service, set out on what was meant to be the crowning achievement of his career: the completion of the Northwest Passage. Commanding the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror—two sturdy ships already tested in Antarctic waters—Franklin sailed from England with 128 officers and crew.

The expedition was one of the best prepared of its age. The ships carried steam engines, reinforced hulls, and thousands of tins of preserved food—enough for three years at sea. Confidence was high, and Franklin, already celebrated as a polar explorer, was hailed as the man who would solve the centuries-old riddle of the Arctic sea route.

After briefly stopping in Greenland, the ships disappeared into the labyrinth of channels and ice of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Their last recorded sighting by Europeans was in late July 1845, when whalers saw them in Baffin Bay, heading west.

By 1846, both Erebus and Terror were icebound near King William Island. According to a note later recovered, Franklin died on 11 June 1847, leaving command to Captain Francis Crozier. The following year, with supplies dwindling and no relief in sight, the surviving crew abandoned the ships and attempted a desperate march south toward the Canadian mainland. None made it.

Back in Britain, Franklin’s wife, Lady Jane Franklin, tirelessly campaigned for search missions. Dozens of expeditions—British, American, and Canadian—scoured the Arctic over the next decades. These searches mapped vast stretches of previously unknown coastline and brought invaluable scientific knowledge, but also grim discoveries.

Inuit oral histories described starving Europeans dragging sledges across the ice, some resorting to cannibalism in their final days. Archaeological finds—bones, clothing, tools, and handwritten notes—confirmed the terrible end. Later scientific studies suggested scurvy, starvation, tuberculosis, hypothermia, and lead poisoning from tinned provisions all played a role in the crew’s demise.

The final chapter of the mystery only came in the 21st century:

These discoveries, made through collaboration between Parks Canada and Inuit communities, have opened a new era of research, with divers and archaeologists carefully studying the wrecks.

Franklin’s expedition ended in tragedy, but its impact was profound. The search for Franklin pushed exploration deeper into the Arctic, advanced science and cartography, and left behind one of the most enduring mysteries of exploration. Today, the story of the Lost Expedition continues to fascinate—an epic tale of ambition, endurance, and the unforgiving power of the polar world.

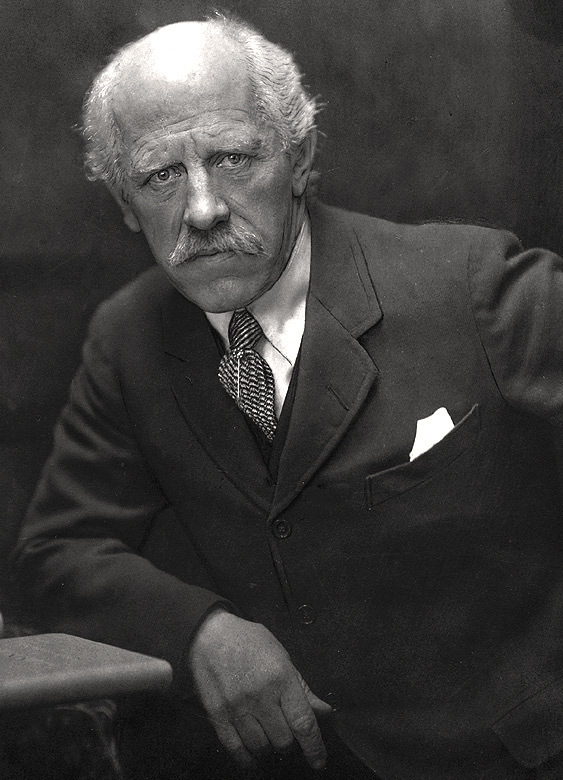

Born near Oslo, Norway, Fridtjof Nansen grew up with a passion for the outdoors. He became an exceptional skier, skater, and naturalist, skills that would later prove vital in his explorations. Trained as a zoologist, he combined science with adventure from the very beginning of his career.

Nansen’s first major expedition came in 1888, when he led a small team on the first successful crossing of Greenland’s inland ice sheet. Instead of following the conventional coastal route, he boldly started from the uninhabited east coast and skied across the ice cap to the west. The journey—over 500 km of dangerous glaciers and storms—proved both his endurance and his innovative approach to polar travel.

Nansen’s most famous polar venture was aboard the Fram, a ship specially designed by Colin Archer to withstand the crushing pressure of Arctic ice. His plan was revolutionary: he believed the Arctic ice drifted across the polar basin, and that a ship frozen into the pack ice would be carried with it.

The Fram later emerged safely from the ice, proving the concept and earning Nansen international fame.

Beyond exploration, Nansen made lasting contributions in oceanography, developing new instruments and theories about currents and deep-sea circulation. His scientific work is still respected today.

After Norway gained independence in 1905, Nansen became a diplomat and Norway’s first ambassador to Britain.

In the aftermath of World War I, Nansen turned his attention to humanitarian causes:

For these efforts, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1922.

Fridtjof Nansen embodied the spirit of the Heroic Age of Polar Exploration, blending daring expeditions with scientific rigor. Yet his legacy extends far beyond the Arctic: as a diplomat and humanitarian, he showed how courage and vision could serve both discovery and humanity.

Today, Nansen is remembered not only as the man who pushed deeper into the polar ice than anyone before him, but also as a symbol of compassion in a turbulent age.

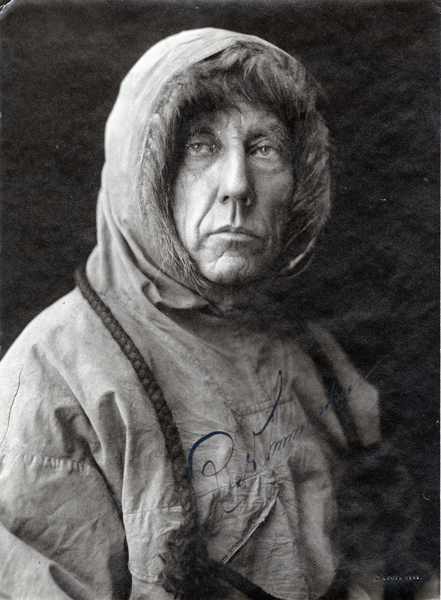

Roald Amundsen was born in Borge, Norway, into a seafaring family. From a young age, he was drawn to adventure and the sea. Initially enrolling in naval training, he later chose a path as a civilian navigator, combining maritime skill with a deep interest in exploration. His early voyages along the Norwegian coast honed his navigation, survival, and leadership skills—tools that would later define his polar expeditions.

Amundsen first gained international attention by successfully navigating the Northwest Passage, a treacherous Arctic sea route linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

Amundsen’s most famous achievement was reaching the South Pole, beating the British explorer Robert Falcon Scott in a race to the Antarctic.

The success was a testament to his meticulous planning, use of traditional techniques learned from indigenous peoples, and relentless attention to detail.

Later, Amundsen turned to aviation and airships to explore the Arctic:

In 1928, during a rescue mission for the Italian explorer Umberto Nobile, Amundsen disappeared over the Arctic while flying a Latham 47 seaplane from Tromsø. His body was never recovered, cementing his legend as a daring explorer.

Amundsen is remembered for:

His expeditions symbolized the Heroic Age of Polar Exploration, marking him as one of history’s most skilled and successful explorers, combining courage, science, and logistical genius.

Born in Plymouth, England, Robert Falcon Scott entered the Royal Navy at a young age, developing skills in navigation, leadership, and discipline. He participated in early naval surveys and gradually became drawn to polar exploration, inspired by the era’s spirit of discovery.

Scott’s first major Antarctic venture was the Discovery Expedition, alongside scientists like Edward Wilson and Ernest Shackleton.

This expedition highlighted the challenges of Antarctic travel and laid the foundation for future exploration.

Scott’s most famous expedition was the Terra Nova Expedition, aimed at reaching the South Pole.

The return journey proved fatal. Scott and his team succumbed to starvation, frostbite, and exhaustion, dying in late March 1912, only 11 miles from a supply depot. Their final written journals and letters were later recovered, providing a poignant account of courage, endurance, and the human cost of exploration.

Scott’s legacy is complex:

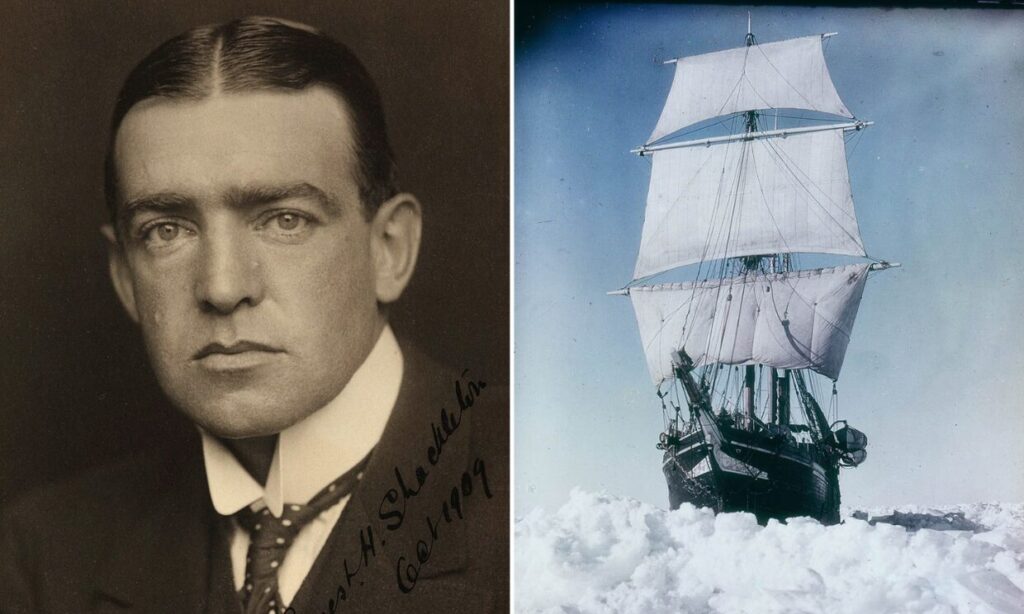

Born in Kilkea, Ireland, Ernest Shackleton grew up in England and developed a love of adventure and the sea at a young age. He trained at the Royal Naval Reserve, gaining experience in navigation, leadership, and seamanship—skills that would define his polar career.

Shackleton first gained Antarctic experience as a member of Robert Falcon Scott’s Discovery Expedition. He participated in sledging journeys into the interior and became seriously ill with scurvy during the return journey. Despite this, he learned invaluable lessons in endurance, survival, and team leadership.

Shackleton returned to Antarctica as the leader of the British Antarctic Expedition (Nimrod).

Shackleton’s most famous expedition was the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, aiming to cross the Antarctic continent via the South Pole.

Shackleton attempted another Antarctic expedition in 1921, the Shackleton–Rowett Expedition, but he died of a heart attack in South Georgia in 1922.

His legacy is defined not just by exploration, but by extraordinary leadership, resilience, and humanity under the harshest conditions. Unlike many explorers of his era, Shackleton is remembered less for reaching specific geographic goals and more for ensuring the survival of his team against impossible odds.

ExpeditionYearsAchievement / OutcomeDiscovery Expedition1901–1904Early Antarctic experience; scurvy illnessNimrod Expedition1907–1909Reached 88°23′S, 97 nmi from South PoleEndurance Expedition1914–1917Ship crushed; 28 crew survived under his leadership

Shackleton is often cited alongside Amundsen, Scott, and Nansen as a defining figure of the Heroic Age of Polar Exploration. His story illustrates that success is not always measured by reaching a pole, but by human courage, leadership, and the will to survive against all odds.

I can now create a full mini-series connecting Franklin, Nansen, Amundsen, Scott, and Shackleton, showing the evolution of polar exploration from tragedy to triumph—perfect for your FRAMTours audience. Do you want me to do that next?

Have you ever dreamed of standing where the ice meets the endless sky, following in the footsteps of legends like Nansen, Amundsen, Scott, and Shackleton? The polar regions are no longer unreachable frontiers—they’re waiting for curious minds, brave hearts, and adventurers ready to explore.

With FRAMTours, you’re not just a tourist—you’re a modern explorer. You’ll witness glaciers, wildlife, and vast frozen landscapes that few will ever see firsthand. You’ll learn the history, science, and stories of polar pioneers while experiencing the thrill of discovery yourself.

Here’s why you should take the leap:

The world’s last great wilderness is calling. Step aboard, feel the crisp polar air, and write your own chapter in the story of exploration.

Your adventure starts here—with FRAMTours, you don’t just visit the poles… you explore them.